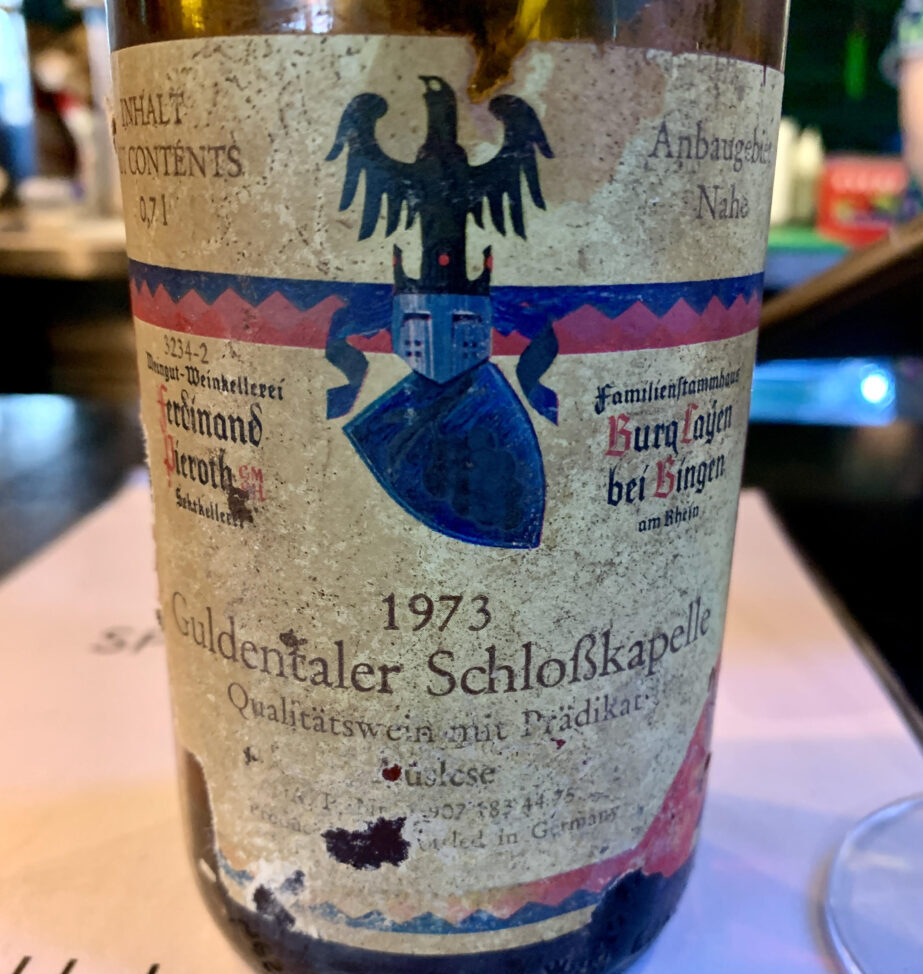

No two bottles of wine are exactly the same. A bottle of wine is a living thing: dynamic, unique and constantly evolving.

This sets wine apart from almost every other drink. Open a bottle of wine today and it will taste different than if you opened that bottle on any other day.

A wine develops in the bottle, gaining in complexity and character, until the day it doesn’t – until the day it can’t – and then it crumbles, falls apart, diminishes and dies.

In the beginning, when wine was fermented and stored in open vessels, young wines were prized wines and old wines were suspect.

Young wines (the decent ones) were fresh and fruity, pleasant to the tongue and nose. Old wines turned sour with prolonged exposure to the open air.

The advent of bottles and corks in the 17th-century delivered a secure means of sealing wine. It meant that a wine could be stored away for lengthy periods and that the effects of time on any given bottle or variety could be observed.

“We are talking not just of a more pleasant or smoother taste,” wrote the wine critic, Hugh Johnson*. “But of a different dimension of taste altogether.”

Not all wines are built to age; few varieties are capable of it. Even among age-worthy wines, bottles must be stored correctly (in a cool, dark and stable environment) and much will depend on how the wine is made and sealed, and the varying characteristics of year-to-year vintages.

When a wine is bottled, a small amount of oxygen (and carbon dioxide) is present and finds its way into the wine. The oxygen acts as a fuel supply to the micro-organisms that make up the flavour and aroma of the wine.

These organisms compete with organic compounds such as tannins, pigments and acids. They combine and shift in a chemical dance that culminates, ideally, in the fine and complex balance of every element.

You enter the dance when you open a bottle and bring to a halt the evolution of a wine. In that sense, you are God. It is you who decides when the music stops. It is you who pulls the cork.

There are both pleasures and frustrations attached to this burden. How do you know when the time is right? How can you tell where a wine is at, on its path to full maturity?

The old trick is to buy a dozen bottles of any wine that ages well and drink a bottle each year, over 12 years, for comparison.

I’ve done that with the Marsanne variety and been stunned by the year-on-year development: from a light, bright and floral wine; to a golden, textured, honey-like nectar.

Other age-worthy varieties? White wines such as Riesling, Chenin Blanc or Semillon. Red wines such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Nebbiolo or Shiraz.

Cabernet is an interesting example. I’m not a fan of young Cabernet: I find it too ‘tight’; too green; too dominated by blackcurrant flavour.

But aged Cabernet (15 years-plus) is something different altogether: an intoxicating, ethereal combination of tastes and aromas; from dry herbs and dusty tannins to cedar and tobacco notes.

The first time I tasted such a wine (an aged, Bordeaux blend), I grasped the concept of synergy – of the sum being greater than the parts. It was a reverential moment; I have never forgotten it.

Wines that are young are typically vivacious, if not a little simple and lacking in depth. Many wines then enter a phase that is strange and hard to fathom: the wines seem inexpressive, surly, flat or lacking somehow.

Beyond this are wines of full maturity: often delicate and fragile, deprived of fruit and force; but integrated, too, with genuine finesse and the most subtle, thrilling flavours, textures and aromas.

I turn 50 in July. This past year, I have had cause to wonder precisely where I am in life: approaching a peak, upon a plateau or – like a wine in its final stage of decline and diminution – somewhere on the downhill run.

Who knows? Only time will tell; it always does.

I am resolved to make the best of things. Forty to fifty was my best decade yet. I want fifty-plus to mean even more.

I will toast that ambition with an aged Cabernet: with a wine from my cellar that has stood the test of time. A wine, no doubt, with flaws and failings – but with power, too, and a certain ready balance.

That’s good enough for me.

* Hugh Johnson, The story of wine (Reed International, 1999): see p.192 for the quote above and for a fine explanation of how and why a wine ages

Image: Age 40; California, USA (2008)

Great Post! Love it. All the best.

Very interesting and well written as always.. Good onya, sir

And here, old mate, is to our next shared bottle! Curly

Nice piece. I hope bottles in my cellar to not get too old to be enjoyed, and me not too old to enjoy them (though I do wonder about the 1998 Seppelt Dorien!)

Cheers, Paul! I’d drink the Dorien now (it’s a Cabernet, right, from old Seppelt vines?): if you’ve stored it right, it should be okay. Enjoy! Paul B

As the saying goes – “I may not know much about art, but I know what I like.”

For me – “I may not know much about wine, but I know what I like to drink.”

Your knowledgeable explanation makes me realise my lack of knowledge on the subject Paul.

So I’ll just raise my next glass of on-special ‘grapes’ & wish you early birthday greetings.

One thing puzzles me though – how come you’re turning 50…& I’m no older (in my head?)! Amazing! A miracle.

Here’s cheers to us both.

Much love, Mum xxxx

You have the energy and vigour of young champagne.

🙂 xx Paul