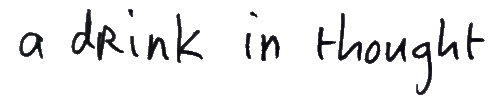

The English artist and art critic John Ruskin was born in London in 1819. Among the prodigious number of projects to which he turned his highly original and generous mind, Ruskin taught drawing classes at a Working Men’s College between 1856 and 1860.

This had nothing to do with drawing well or with teaching others to become an artist. Nor did it bother Ruskin that few of his students might ever produce a work of art good enough to hang in a gallery.

“My efforts are directed not to making a carpenter an artist, but to making him happier as a carpenter,” Ruskin said.

Ruskin (pictured) taught drawing because drawing compelled his students to stop and pay attention to the object of their sketch. Can you draw a crab in all its strange and brilliant detail if you haven’t looked closely at a crab?

Ruskin asked his students to slow down and take notice.

For Ruskin, the world was abundant with every sort of beauty – from crabs and sprigs of parsley to mountains, lakes and trees. Too often, we fail to see the beauty. We rush past, oblivious.

In doing so, thought Ruskin, we deprive ourselves of a profound and inexhaustible source of solace, joy and inspiration. Pay attention and reap the rewards.

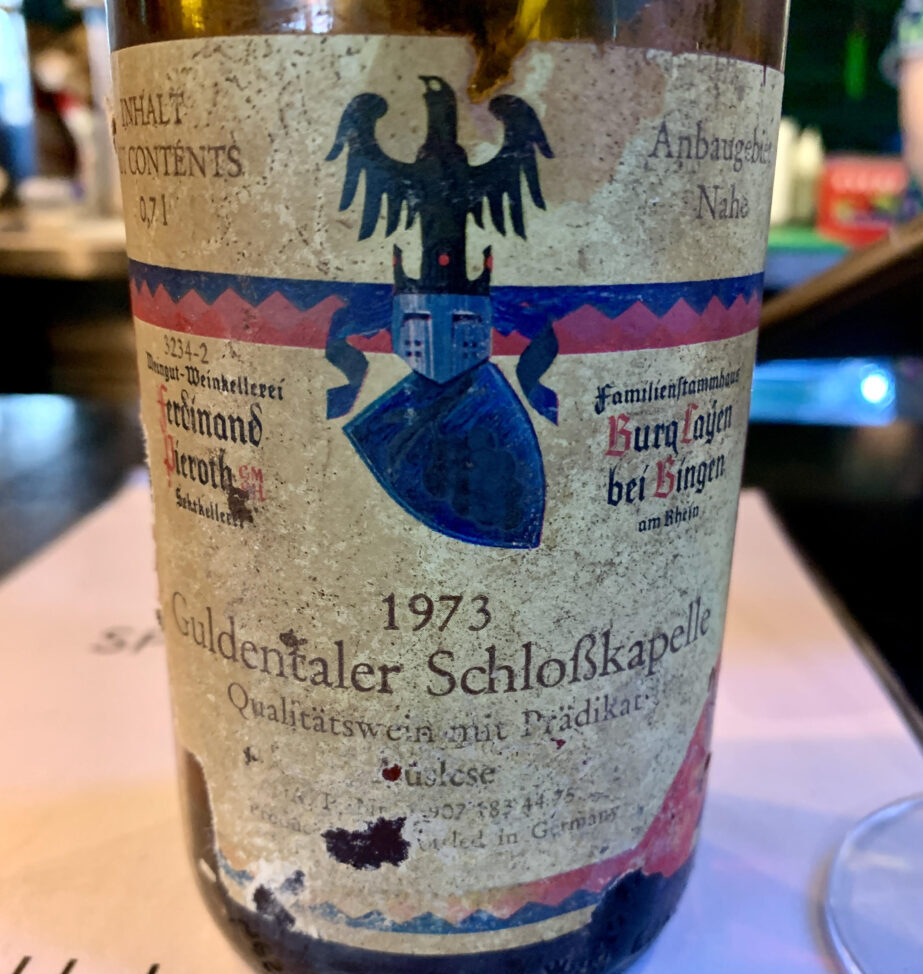

That’s how I feel about wine. You can drink it without thought or attention; most of us do, most of the time. Nothing wrong with that. But the rewards of attention are immense.

Among those who claim to have no palate or sensory appreciation, I place before them a glass of wine. I ask them: is it red or white? Let’s say it’s white. No one gets that wrong.

I ask them to smell the wine. Is it earthy, floral, fruity, nutty, savoury or sweet? Everyone discerns at least one of those options. Let’s say fruity.

I ask them: do you mean stone fruit or citrus-like? Do you mean dried or tropical fruit?

They smell the wine. They taste the wine. Their mind goes in search of memories relating to the fruits – of the last or most profound occasion on which they consumed these fruits. Perhaps they nominate tropical.

I ask them: do you mean banana, lychee, melon, pineapple or something else? They say pineapple. I push them further: do you mean freshly cut or tinned pineapple?

They apply themselves; I see them straining with the effort. I ask again: freshly cut pineapple, a little lean and sinewy? Or tinned, sweet and a little viscous?

They recall a time from childhood when their grandmother served them ham and cheese on toast, topped with bright yellow chunks of moist pineapple, the pieces lifted with a fork from a 500 gram tin.

And there you have it. A complete novice has taken a glass of wine and delivered, within minutes, a precise and compelling assessment. Not bad for someone who claimed to have no palate.

Yes, they were guided to some extent – but so what? They won’t need me next time. They’ll trust themselves. They’re away…

The work of attention is difficult. It requires that we set aside our preoccupations long enough to concentrate on a single object – a glass of wine, a leaf, a crab – and to notice that which we have already seen but never truly registered.

Give it a try. Not in order, necessarily, that you may be a better wine taster, but that you may be happier, and at home, in a world of beauty and abundance.

For an elegant introduction to the life and work of John Ruskin, see The Art of Travel by Alain de Botton (Penguin Books, 2003; pp.217-238)

Delightful, both the drawing and drinking. I would be one who needs a palate coach. Let us know if we can sign up for a tasting!

You’re lovely. And will do! Thanks, Julie. Paul