Ilove books and wine in equal measure. I love books about wine, especially.

At our house, wine is stored in the same room as a small but ever-growing library of wine literature: a dedicated shelf of wine guides, atlases, histories, criticism, journalism, tasting notes, travelogues and memoirs.

Wine writing attracts a fair amount of criticism on the grounds that it can be pompous or that it fetishises wine and tends to pedantry.

That, to me, depends on the author; a crushing bore is a crushing bore whether they like wine, football, politics or poetry.

Perhaps the only advantage of bad writing is that it makes the good stuff easier to spot.

The American writer Frank Priall said: “Wine writing is plagued by hyperbole; a sort of phylloxera of the written word that spreads fast and is tough to root out.”

I love that line because it is true and because, as a piece of literary criticism, it is good writing.

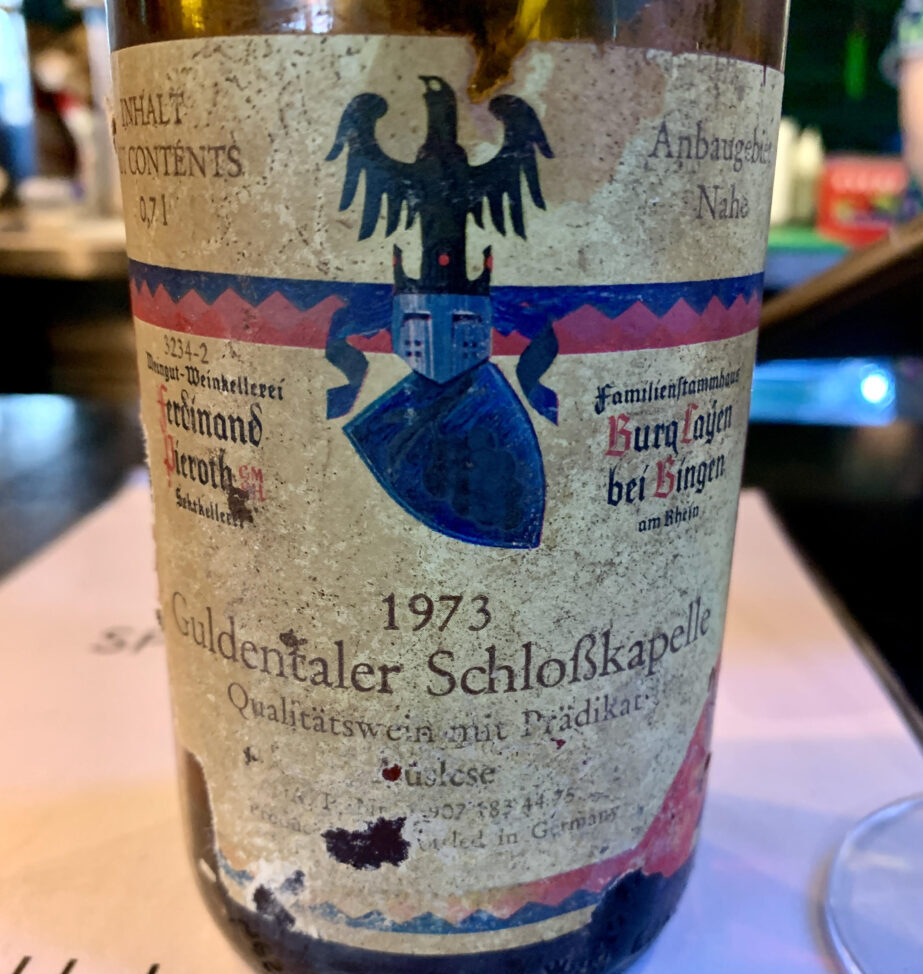

To some extent, I read about wine because it is useful. Wine is a subject that tends heavily to classification and categorisation: wine styles, grape varieties, viticultural regions, quality designations, tasting scores and vintages. I read because the effort yields accelerated learning.

Mostly, I read for the joy it. I like how it feels: the physiological response to words on a page; the moment when a line of text shoots to the brain unexpectedly, then ricochets back through the body to somewhere in my gut.

Like when I read this: “Farmer and artist, drudge and dreamer, hedonist and masochist, alchemist and accountant – the winegrower is all these things, and has been since the Flood.”

Hugh Johnson wrote that in his epic history, The story of wine. The line is so good, he used it twice: it is the opening and the closing sentence of his monumental book.

Johnston is possibly the world’s best-selling wine writer and certainly one of its best known and most prodigious.

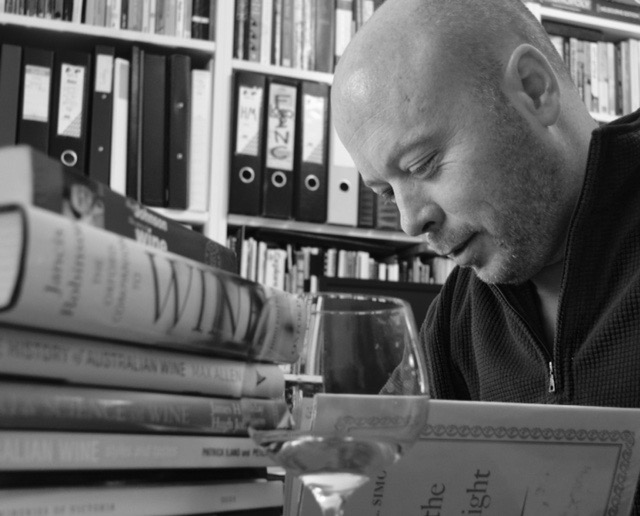

When he was young, Johnson helped a man called Andre L Simon bring a book into the world. The book, In the Twilight, was written when Simon was 92 and going blind. “Old age [has] caught me at last,” Simon wrote.

Simon (1877-1970) was a French-born, English wine merchant, gourmet, educator and prolific wine writer.

Johnson describes him as “the charismatic leader of the English wine trade for almost all of the first half of the 20th-century, and the grand old man of literate connoisseurship for a further 20 years”.

No biographic note does Simon justice; he lived a huge life and appears to have loved every minute of it.

He wrote more than 100 books on a vast range of subjects in his 66-year writing career: he wrote a history of the champagne trade in England; compiled a best-selling encyclopedia of gastronomy; founded the English Wine and Food Society Journal; and wrote a best-selling guide to Russian grammar.

There was seemingly no limit to his range of interests or to the excitement and generosity he brought to those interests.

Simon visited Australia in 1964 and celebrated his 87th birthday among friends and admirers in Western Australia. The occasion involved a long lunch with “wines and speeches galore.”

The following year, he travelled to South Africa for a birthday celebration that lasted three days and made a large dent in the champagne stocks of Cape Town.

My edition of In the Twilight includes a photograph of Simon taken late in his life. He is sitting in a garden chair, holding a glass of wine. He has white hair, wrinkled skin and a friendly, easy smile.

Why is In the Twilight so good? It is not so much the writing as the man himself. Simon knows his life is blessed, and his gratitude is real and ever-present.

“No complaints! I am ready to go,” he writes on the final page. “I have had more than my fair share of all that is best – faith, affection and good health, three wonderful gifts no money can buy. I have worked hard as long as I could see, and loved it.”

In the end, it is Simon’s voice that draws you in because Simon himself is a man of such obvious energy and warmth, with a gift for storytelling and a crowded life on which to reflect.

Simon believed that “a man dies too young if he leaves any wine in his cellar.”

At the time of his death, Simon’s once considerable cellar contained just two magnums of wine.

On what would have been his 100th birthday, in 1977, 400 guests gathered at the Savoy Hotel in England to drink to his memory with a Château Latour 1945 that he had left for the occasion.

I wish I could have been there.