On the morning of our second day in the Tamar Valley, Tasmania, we gathered by the Tamar River on the western side of the valley. The day was calm, clear and bright.

The river held upon its surface an image of the sky – an image so tranquil and precise that river and sky appeared as one.

We stared across the water to the low line of green hills on the valley’s eastern edge and admired the homes among the trees that face towards the river. We imagined living there.

Noises carried across the water from every corner of the valley: the low, staccato grumble of a truck changing gears; the sound of human voices.

There were five of us – five mates from the mainland – and now and then a passing local, led along the river’s edge by a busy dog on a straining leash.

We were there on a two day wine trip, lining up at cellar doors on both sides of the valley.

We came in search of sparkling wines and found them in abundance; the most delicate and complex wines the country has to offer. We drank Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and aromatic white wines.

I am pretty sure I once read that the Australian wine writer and industry legend James Halliday said that if he was starting over and planting vines for the first time, he would do so in the Tamar Valley.

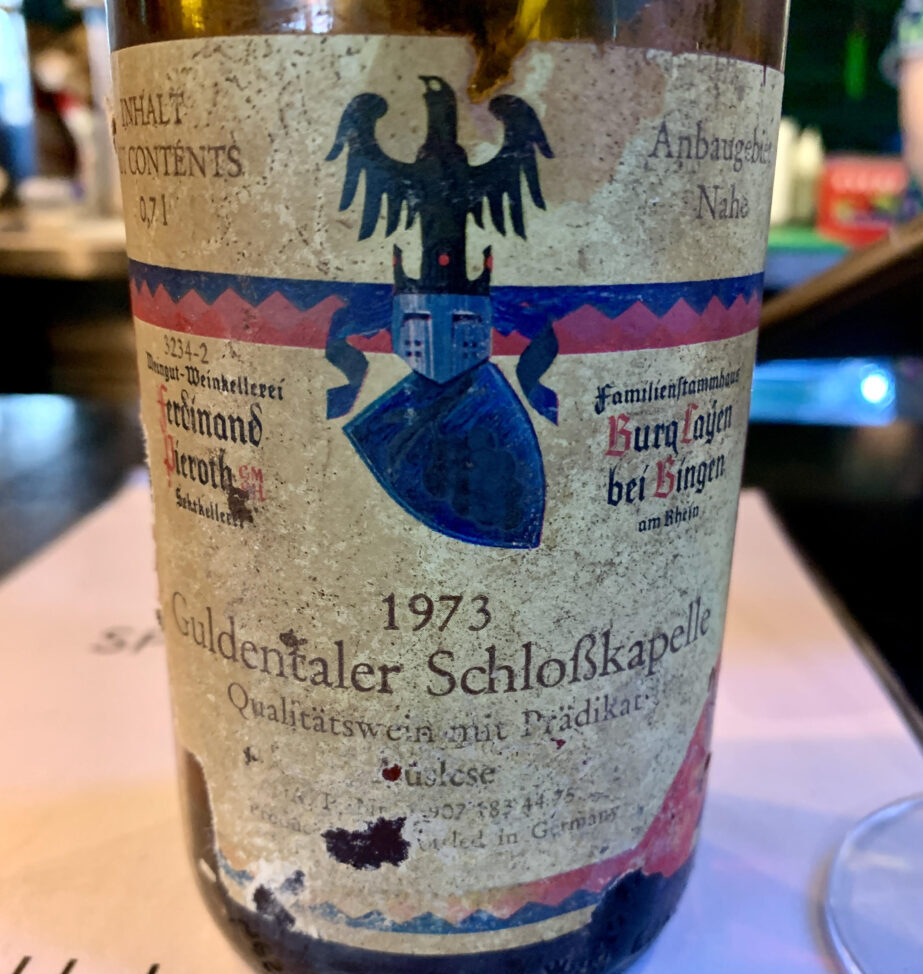

I can see why. The climate is comparable to that of Champagne, France, and the Rhine Valley, Germany.

The region holds within its spread a stunning diversity of microclimates and geographic variation.

The long, cool growing season allows for the gradual accumulation of fine and elegant flavours within grapes and the retention of natural acidity, a vital component of the best sparkling wines.

At every turn, on both sides of the valley, when the broad sweep of the cool river comes in to view, the effect is monumental – especially on a cloudless day when sunlight hits the water and the river glistens like a diamond.

And the wines? In the sparkling wines alone I tasted lemon, pear, apple, spice, honey, ginger, butter, fig, grapefruit, peach, candied orange, almond meal and brioche.

I ceased recording flavours when my vocabulary faltered, fully aware that I was still alert to layers of taste and complex aromas for which I may never find words.

On that second morning by the river, I told the boys about the debt that Victoria and South Australia owe Tasmania’s wine industry – a story I’d read in Halliday’s Wine Atlas of Australia.

When the pastoralist and pioneer William Henty sailed from Launceston to Portland, Victoria, on board the schooner Thistle in 1834, his personal effects included “one cask of grape cuttings and one box of plants.”

Other Tasmanians headed further west, carrying with them cuttings from home. I tried to picture it: did they pass the spot where we now stood as they swept up the river towards the sea, almost 200 years before?

It took anywhere up to a fortnight to cross Bass Strait by boat in the 19th-century.

It took anywhere up to a fortnight to cross Bass Strait by boat in the 19th-century.

We flew back to Melbourne in less than an hour, bottles of wine in the overhead compartment.

Departing Launceston, our plane climbed above the valley and flew north along the river. The last light of day lay upon the water.

From high in the air, the river weaved like a bright ribbon towards the sea and the sun cast its dying glow on the edge of the horizon.

Main image by Matthew van Hasselt, 2016; Image insert by James Bateman, 2016

Wineries visited: Jansz; Bay of Fires; Delamere; Holm Oak; Tamar Ridge; Josef Chromy.