In October 1929, when she was 47, the celebrated English writer Virginia Woolf published the extended essay A Room of One’s Own, with its famous dictum: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

The essay was based on a series of lectures Woolf delivered at two women’s colleges at Cambridge University in 1928.

Woolf’s essay, widely considered a landmark of 20th-century feminist thought, explores the history of women in literature through an examination of the pre-requisites required for writing literature – such as leisure time, privacy, financial independence and intellectual freedom.

Throughout history, Woolf concludes, women have been consistently and profoundly deprived of those social and material prerequisites.

I read the essay because of Judith the cat. Judith belonged to a woman I knew. The woman was a fan of Woolf’s writing.

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf (pictured) says: “Let me imagine, since facts are so hard to come by, what would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith…”

That’s how the cat got her name. And that is how I came to own a copy of Woolf’s essay.

I love everything about the essay, but here are three specific things.

One, Woolf’s voice: direct and confident.

Two, Woolf’s central argument: meticulous and logical.

Three, the story of Shakespeare’s imagined sister: brilliant, tragic and utterly believable.

In the end, the talented and spirited Judith – no less capable or ambitious than her famous brother – is doomed to fail because of her gender; the world is made for William, not Judith.

“That, more or less, is how the story would run, I think, if a woman in Shakespeare’s day had had Shakespeare’s genius,” writes Woolf.

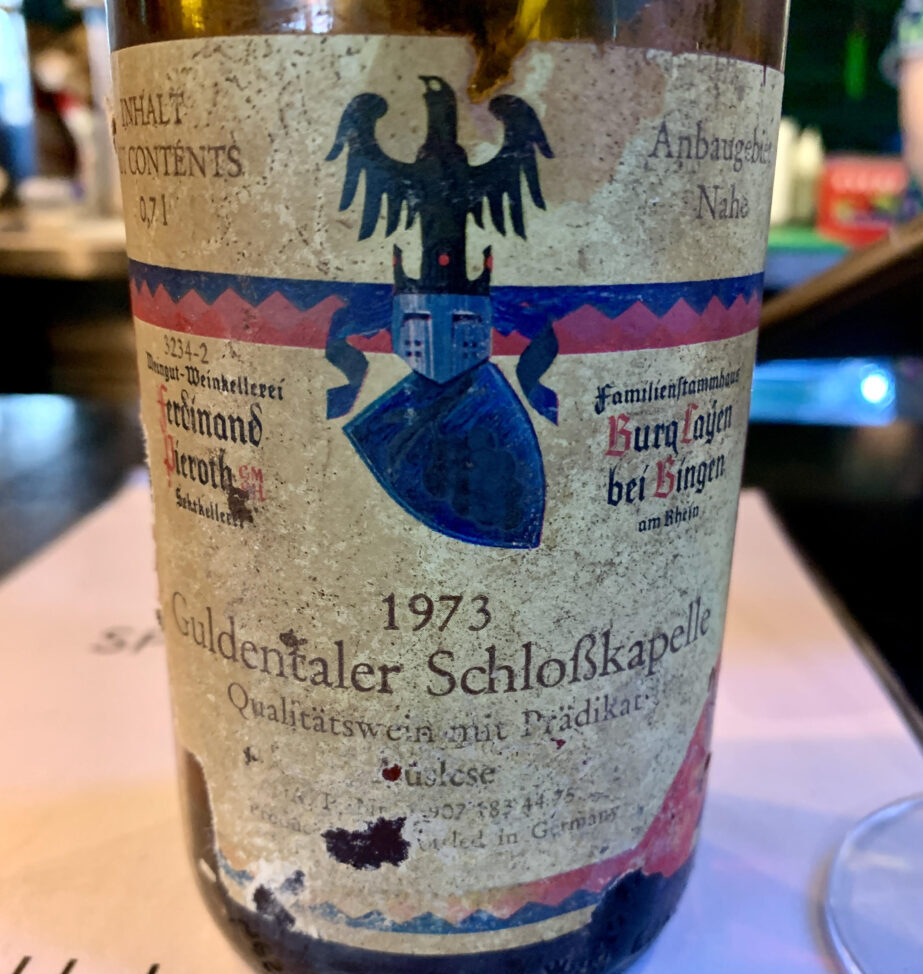

All of this came back to me on a trip to north-west Italy in July 2015. At a cellar door near the city of Alba, I was told the story of Arneis, a native varietal wine of the Piemonte region.

Arneis means ‘little rascal’ in Piemontese dialect and is so named because it can be difficult to grow; that much I knew already. But that is only half the story.

Arneis is a low-yielding variety with inherently low acidity, sometimes oaked, but rarely. The use of oak produces a fuller-bodied white wine with aromas of pear and apricot.

Unoaked, the wine is dry, crisp and freshly scented – think white peach and floral notes. In the heat of that Italian summer, it was my ‘go-to’ white wine.

In Piemonte, however, red wines get most of the attention. This is the home of the Nebbiolo grape and the great wines of Barolo and Barbaresco.

For many years, wines like Arneis played a supporting role. Often they were used in small amounts to soften the tannins of the Nebbiolo grape: Piemonte’s answer to the Shiraz/Viognier blends of the Cote du Rhone.

It followed that the better situated vineyards of Piemonte were planted with the prized Nebbiolo grape, leaving the lesser sites for Arneis.

Adding insult to injury, Arneis was often planted in an effort to attract birds and insects away from the Nebbiolo grapes – never mind producing wine.

So low were its stocks that in the 1970s, Arneis was on the verge extinction. At that point, one or two producers began bottling their excess Arneis, bringing to the process the kind of liberating disinterest that typifies those with nothing to lose.

The results were encouraging; Arneis could stand alone. What if its vines were planted on better sites, in premium soil, with care and attention?

And so it happened. Given a paddock of its own and the chance to express its unique qualities, Arneis flourished.

The 1990s saw an explosion of interest in Arneis and production quadrupled. Today, the wine is officially recognised and protected by Italy’s highest quality wine designations.

And Virginia Woolf? Throughout her life Woolf suffered from deep bouts of depression. Upon completing the manuscript of her last (posthumously published) novel, Woolf succumbed once more.

On 28 March 1941, at the age of 59, Woolf drowned herself. She filled her overcoat pockets with stones and walked into a river near the house she shared with her husband, in the English countryside. Her body was found three weeks later.

Whenever I open a bottle of Arneis, I remember Shakespeare’s imaginary sister and the loss she represents.

I think about the struggle we face on the road to independence and the pre-conditions we each require for growth and self-expression.

I think about Virginia Woolf and offer up a heartfelt toast.