If he thought too much or dwelt too long on the purpose of his life – on questions of existence or the meaning of lost time – he almost always led himself to some dispiriting conclusion.

Lodged within his psyche, in the depths of his subconscious self, lay a melancholic impulse that manifest its shadow in times of stress or weariness.

This impulse stained his view of things, distorting and diminishing his quality of life. He compromised the future with fierce bouts of futility, and no amount of thinking could arrest his fall from joy.

If, however, he left the house – if he took a walk outside – he almost always found his rhythm and felt those doubts subside.

When he went about his business, when he did the task at hand, he was almost always cheerful, positive and true.

If he passed a stranger on a quiet street, he would smile and say hello. He never gave it any thought; his instincts were his guiding star.

What had he learned? What must he remember in times of angst or apprehension?

He must value action over thought. He should trust himself and apply himself to the immediate and real. He should worry less and whistle more.

But this was 2021 and the world had shrunk in direct proportion to the magnitude of a global health pandemic. For much of the year, he was confined to home by a city-wide lockdown that curtailed his engagements and constrained his energies.

He threw himself into his work, grateful for the income at a time of widespread loss, but the work was all-consuming and somewhat disconcerting.

He engaged with his colleagues from a digital distance, which robbed their work of context and the spark of human contact. By day’s end, he felt as drained as an old battery.

There were countless jobs around the house, but none that held his interest. In any case, he wasn’t good with tools. He would never build a bird bath or wire-in new downlights. He couldn’t fix the plumbing or install a set of shelves.

He could write a bit, and he often did, but it meant more hours at his desk and even further introspection. The thought of it exhausted him.

He could write a bit, and he often did, but it meant more hours at his desk and even further introspection. The thought of it exhausted him.

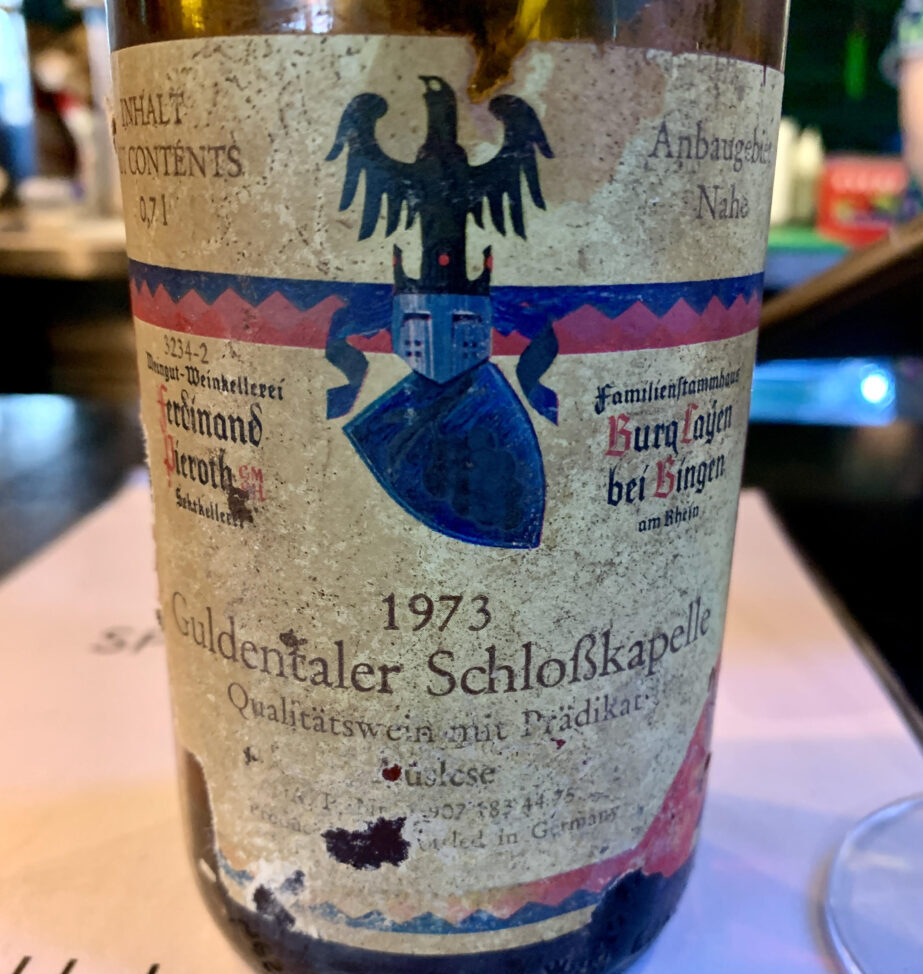

He liked to cook. He liked to eat. He owned a small collection of fine and treasured wines. Could he join these things together in a way that brought him peace? Could the kitchen soothe his restlessness or focus his attention on a single, satisfying task?

He thumbed his way through recipe books, compiling menus in his head. He set aside whole chunks of time to shop for strange ingredients. He tied an apron around his waist and urged himself to settle: Be here now, mate. Be here now.

He loved the bright and solid certainty of pots and pans and heavy knives. He loved the necessary chemistry by which a thing becomes another thing: how the flavour of an onion is transformed from sharp to silky-sweet, when diced and slowly cooked.

Cooking, he discovered, encourages imagination and rewards commitment to the craft. He was sure of his expanding palate and the insights it conveyed. He found a new vocabulary, a language for his sense of taste.

There was a time, many years ago, when he lived in an old weatherboard house and claimed, for himself, a shed in its yard. He worked from the shed throughout the night, writing and sketching.

Possums came to visit him. Moths fluttered high above his head, circling and colliding with an exposed electric light bulb.

Possums came to visit him. Moths fluttered high above his head, circling and colliding with an exposed electric light bulb.

He worked until the sun rose, until his body ached and his eyes were shot. He staggered from the shed, reeling with exhaustion, and lay beneath a lemon tree, face-to-face with the morning sky.

Sketching was his ‘second’ art – a thing he did without much thought or critical self-censorship – and therefore he was happy and worked in an expansive way.

The pen, his hand and the sketching pad existed as a single force; their relationship was magical, tactile and direct. He gripped the pen and moved his hand across an open page. Images inside his head appeared as living shapes.

Now, when he cooked, the memory of those distant nights returned to him with poignant force. Here, once more, he freed his mind by working with his hands: dicing carrots, sprinkling salt, rolling pastry, kneading dough. He found his equilibrium.

And then it was time to eat.

He lived with his wife in a small, two-bedroom home. They worked throughout the day at opposite ends of the house, but met for lunch and dinner around the kitchen table.

Not every meal was leisurely – not every meal was art – but every time they gathered, he felt replenished and restored.

They renewed their deep communion over plates of food and matching wines. It seemed to him that at their best, they occupied a timeless space in which the warmest and most carefree thoughts rose freely from the table.

To eat and drink together was a sane and simple pleasure: a joy beyond philosophy, theory or abstraction; a remedy for lethargy and the strain of daily life.

Once, when he was feeling low, his wife shared with him a Chinese proverb: A bird does not sing because it has an answer. It sings because it has a song.

That night, he cooked risotto and popped the cork on a bottle of champagne.

Images from the kitchen, 2021: Basque burnt cheesecake; Crème caramel; Malay eggplant curry; Egg yolk ravioli; Mushroom risotto, chicken sausage, balsamic reduction; Champagne Pol Roger